Today, I had the pleasure of attending the online conference on Public Health and Positive Psychology in times of COVID-19. One talk in particular caught my attention: Dora Gudmundsdottir, Director of Public Health in Iceland and current President of the European Network of Positive Psychology (ENPP) was talking about health and wellbeing before and after COVID-19 in Iceland.

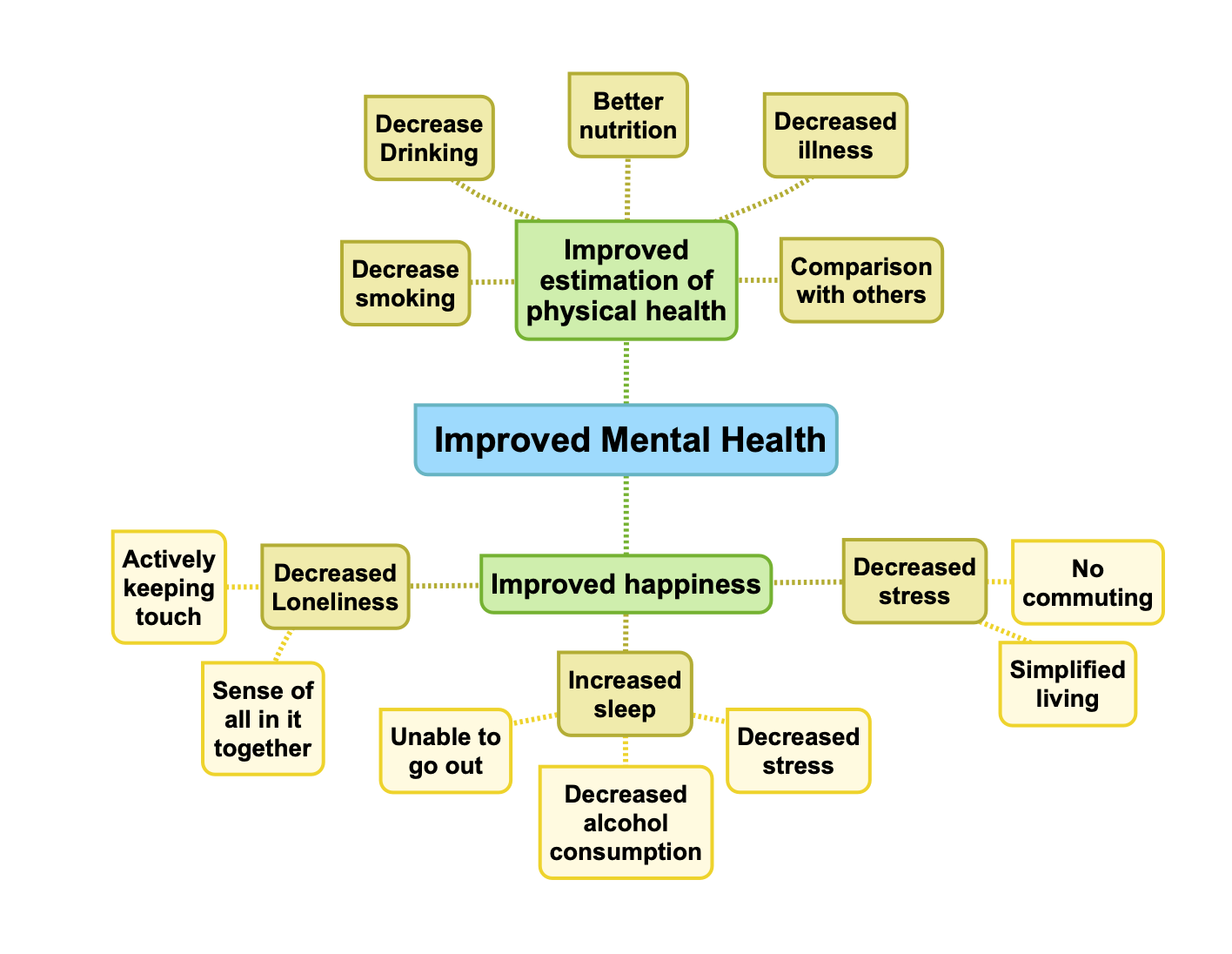

Iceland carries out monthly surveys of its population including self-reported measures of physical health, mental health, sleep, happiness, loneliness and stress. They have been doing this for years, and on the whole, although levels of each vary slightly, they are fairly stable. Then COVID-19 struck Iceland. What happened next was a surprise. Over the peak of the pandemic in, when people were locked down, their estimation of their physical health improved, with a significantly higher number describing their physical health as Very Good (there were four levels, this being the highest).

So, what was happening?

It is probably too early to fully understand, but two factors are likely to have played a part: 1) By being locked down, people were exposed to fewer other diseases 2) In comparison to those with COVID-19, people reckoned they were doing okay.

Additional factors that could have also contributed were that people were suddenly incredibly aware of their health, and what they could do to improve it. Smoking and alcohol consumption decreased while healthy eating may have increased.

So that was physical health, what about mental health over lockdown?

Again, the results were not quite what was expected. People’s estimation of their mental health was stable throughout March and April this year during the peak of the pandemic. They were comparable to January and February or even March and April of last year. Then, as lockdown eased in May, it dropped significantly. Digging deeper, when we examine Icelanders’ self-reports on happiness, this peaks in April 2020, plummeting as the country opened up in May. The same went for sleep, while for loneliness and stress, the effects were reversed.

That sleep improved over lockdown is not a surprise, with less to do people have earlier nights and with a shorter commute to the living room than the office people can sleep in longer. Decreasing smoking and drinking would also improve people’s sleep. Lockdown itself could have resulted in people’s loneliness decreasing as they actively kept in touch with friends and family over online platforms, while feeling an increased sense of belonging as the nation worked together against the disease. The easing of lockdown may have decreased the effort people put into keeping in touch and the anxiety of being in close physical proximity in the face of an invisible disease could have increased stress.

I suspect that given a couple of months, the silver lining of improved physical and mental health seen in Iceland will, on the whole, revert back to ‘normal’ levels. But for some, the eight to ten weeks of lockdown will have been long enough to have established new, healthier habits that people can see the benefit from. After all, it is easier to replace an unhealthy habit with a healthy one rather than just trying to stop it cold.

If you would like to talk about how you can maintain some of the healthier habits you adopted during lockdown, contact me for a no-strings chat about how coaching can help you.